Hypothesis #1: Subjective Mystical Experiences

In a previous post I wrote about the idea that the antidepressant effects of psychedelic drugs could be related to a "loss of self," in which people are able to see their lives from an outside (or even "universal") perspective. An LSD study showed that some of the strongest subjective effects of the drug (besides its perceptual alterations) involved an experience of unity with the world, a blissful state, a sense of meaning, and a feeling of "ineffability" or insights that could not be put into words. Mystical experiences are also one of the most commonly reported subjective effects of psilocybin. In a study of ayahuasca, another psychedelic drug, people who reported stronger perceptual disturbances and mystical experiences also had greater improvement in their depressive symptoms. Similar findings have been reported for the antidepressant effects of LSD, with mystical experiences during a single LSD administration again emerging as one of the strongest predictors of positive mood changes up to 12 months later, although in this case the participants were not initially diagnosed with depression. In a review of 12 psychedelic studies, 10 found that mystical experiences predicted antidepressant effects, on the basis of either correlations, mediation analyses, or predictive tests. Out of several dimensions of mystical experience, this systematic review showed that the ineffability factor was the most consistently related to symptom improvement, with subjective meaning as a second important sub-dimension. Many of these mystical experiences have strong similarities to what people report during a near-death experience (NDE), which can have similarly life-changing effects on people's behavior.

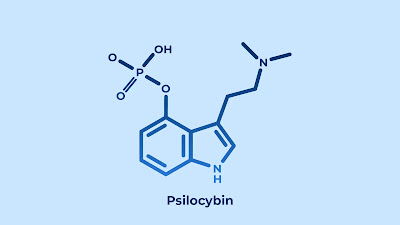

In a mouse study, researchers were able to isolate the antidepressant effects of psilocybin from its effects on the serotonin system in the brain, which is one of the usual biological explanations for depression. (For instance, widely used medications like fluoxetine [Prozac] and sertraline [Zoloft] work by increasing the availability of serotonin in the brain). Serotonin is also likely responsible for the perceptual distortions that people usually experience when using psilocybin. Interestingly, the mouse researchers found that even when the serotonin response was inhibited with another drug, psilocybin still led to behavioral changes in mice that were consistent with them being less depressed. This might suggest that the "mystical experiences" pathway is actually a different way to achieve antidepressant effects than most of the drugs currently available that work via the serotonin system.

Hypothesis #2: Disrupting Brain Networks

One of the oldest antidepressant treatments still in use is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which also has benefits for people with treatment-resistant depression - in this case, in a head-to-head study against ketamine used with a similar group. The reasons why ECT works aren't completely understood either, but two major hypotheses are (a) that it creates inflammation which provokes a healing response, analogous to the body's natural process for recovering from injuries or surgery, or (b) that it disrupts existing networks of brain activity which makes room for new neural patterns to be established via neuroplasticity. Patients' subjective experience of ECT is that it temporarily disrupts memory formation and conscious thought, leading to improved mood and concentration afterwards. Some research also shows that lower-level electrical brain stimulation can improve concentration and focus in people with cognitive problems, by encouraging neurons in different areas of the brain to fire in sync.

Psilocybin has a similar disruptive effect on people's reactions to the external environment, as well as to their sensory experiences. As in the case of ECT, disruption of existing networks could be therapeutic, based on the assumption that a person's current brain patterns are leading to suffering and that they might come back in a different and less disturbing configuration. Two recent studies of psilocybin showed significant decreases in brain network modularity (i.e., less inter-connection between different regions of the brain) at 1 day after psilocybin administration, and that the level of initial disruption then predicted level of improvement in depression symptoms at 6 months based on a standard questionnaire. A third study looked at people's cognitive flexibility based on a task that required "shifting sets" (e.g., the rule for correct answers changes from "match the shapes" to "match the colors" without notice, and the question is how many repetitions it takes someone to catch on). This study found that people's level of flexibility increased after 2 doses of psilocybin taken a week apart, and that improvements in flexibility were related to decreased brain modularity and increased whole-brain connectivity based on fMRI scans completed 4 weeks after the second dose of psilocybin. Disrupting existing patterns might in turn create a new openness to learning: One study of mice suggested that this might increase susceptibility to social reinforcement back to a level that normally would be seen only in the "critical period" for learning that existed earlier in life.

The disruption of more specialized neural modules may then be replaced by a more holistic "global integration" or "coherence" of the entire brain's neural patterns, as seen in a study that showed more flexible and broad linkages of brain areas up to 3 weeks after people received 2 doses of psilocybin plus a standard antidepressant medication. In addition, people with greater re-organization of their brain patterns based on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans also showed a greater reduction in their symptoms of depression. A second fMRI study from the same team found similar results, and showed that a more traditional antidepressant medication did not produce the same type of brain-integration effects. A study using electroencephalography (EEG) also showed greater global coherence across brain regions, particularly in the gamma brainwave spectrum (very fast cycles of 25 Hertz or more), during ayahuasca use. The authors suggest that increased linkage across diverse brain regions might be responsible for the common experience of synesthesia during psychedelic use. As a final source of support for this hypothesis, increases in coherence on other body measures such as heart rate or breathing seem to correlate with EEG coherence, and also to predict improvement in mood and cognitive functioning.

Hypothesis #3: Decreased Fear Response

The third hypothesis about psilocybin's effects focuses on a specific brain region, the limbic system. This is a component of the Intuitive system that's located deep in the brain, and includes structures like the thalamus, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and amygdala. These parts of the brain manage our primitive emotional responses like fear and desire, and often have powerful motivating effects on our behavior. Psychedelic drugs may have particularly strong inhibitory effects on these systems; for example, one study found that people taking psilocybin were less likely to startle in response to a loud bang, and that this inhibited startle response was again associated with mystical experiences. And a second study using fMRI imaging found that people had a reduced cortical brain response (i.e., less activation of the Narrative system) during an "oddball task" that required them to differentiate between usual and unusual perceptual stimuli. One way of interpreting this second study's findings is that under the influence of psilocybin, people found the unusual to be pretty normal! The level of decrease in people's response to unusual perceptions was also directly related to their scores on mystical experience subscales measuring "disembodiment" and "unity with the external world," so there might be some connection between fear disruption and mystical experiences as reviewed in hypothesis #1.

Brain-scanning studies using fMRI have also shown changes to the limbic system in particular during psilocybin use. A 2017 study found decreased blood flow to the amygdala and other limbic-system areas after 2 doses of psilocybin, which were still observable up to 5 weeks after the second dose. This specific reduction in limbic activation was combined with increased whole-brain activation, similar to the EEG and other studies reviewed above. And most significantly, a series of studies involved showing people a series of pictures while they were in an fMRI machine. People who see negative images generally have a strong amygdala fear response, while people who see neutral or positive images do not. In a 2015 study of healthy volunteers who received 2 doses of psilocybin, brain activity in the amygdala actually decreased while they were viewing neutral or negative images under the active influence of psilocybin, with no changes in other brain areas such as the primary motor cortex. This pattern of activation might suggest that these people's brains were responding to the negative images with a different emotion, like interest or curiosity, instead of fear and loathing. A 2016 paper from the same team presented additional data showing that the amygdala also became less connected to the primary visual cortex under the influence of psilocybin -- similar to hypothesis #2 about changes in brain connectivity, but specifically showing that threat perceptions and visual perceptions became less strongly linked to one another. Such changes in a person's intuitive threat response could be particularly important in helping people to overcome conditioned responses due to trauma in which an originally neutral stimulus has come to have very strong negative associations.

The last two studies in this review used an even more specific visual prompt, showing people in an fMRI scanner pictures of people's faces where the expression was happy, neutral, or fearful. Faces are a particularly strong emotional stimulus because humans are strongly oriented toward what other people think, with "mirror neurons" in the brain firing in sync with the emotion that we perceive from another human's expression. In a 2020 study, people with treatment-resistant depression received 2 doses of psilocybin a week apart, and showed decreased connectivity between the frontal lobes and the amygdala (in other words, between the Narrative and the Intuitive systems) in response to fearful or neutral faces. The amygdala became more connected, on the other hand, with visual areas of the cortex -- an opposite pattern from what was seen with healthy volunteers. As in other psilocybin studies people's depressive symptoms improved, and lower levels of connectivity between the amygdala and cortical areas predicted particular improvement in the "rumination" component of depression -- the tendency of depressed people to go over and over negative thoughts in their minds. This is another example in which reduced synchronicity between particular brain areas might be helpful, if it breaks a cycle of negative thoughts and emotions that reinforce one another over time. Finally, a 2018 study also showed faces to people with severe treatment-resistant depression, and showed whole-brain changes in connectivity that were associated with symptom improvement. In this study, however, a stronger amygdala response was seen to both fearful and happy faces after administration of psilocybin. Other methods (dosing and follow-up schedule) were similar across the two studies, and the patients were similar, so this is a somewhat anomalous finding. Why should it be that people whose amygdalas responded more strongly to a fear-inducing stimulus would report greater improvements in depression? These two studies were actually done by the same team, and the authors suggest that psilocybin is "restoring emotional responsiveness," but in general the literature seems to suggest a different interpretation, that fear responses are being suppressed while overall brain integration increases.

Conclusions

The three hypotheses discussed above are not necessarily incompatible with one another. The fMRI studies have mostly focused on (a) disruption of existing brain networks and (b) increased connectivity between disparate brain regions, although there is also a strong element of fear reduction. The behavioral effect of disrupting existing patterns seems to enable more flexible thinking and curiosity about new experiences, which might facilitate new learning or the reversal of self-protective behavior or ruminative thoughts. And what all of this feels like from a subjective point of view may be a mystical experience, with particular elements of ineffability and meaningfulness. All three of these components predict people's level of improvement in depression, when the participants in a study are depressed individuals who receive various psychedelic medications. Findings from healthy volunteers are generally also supportive of these three mechanisms. Most intriguing is the suggestion that some of these effects might be distinct from the serotonin mechanism that produces perceptual distortions -- the characteristic "tripping" experience of psychedelics. Future research will probably shed additional light on the brain processes that facilitate rapid improvement in depression with psychedelic drugs, which can help to make these treatments safer and more predictable, and might even increase our understanding of the Intuitive-mind pathways by which other treatments such as talk therapies have their effects on people with psychological problems.

Comments

Post a Comment