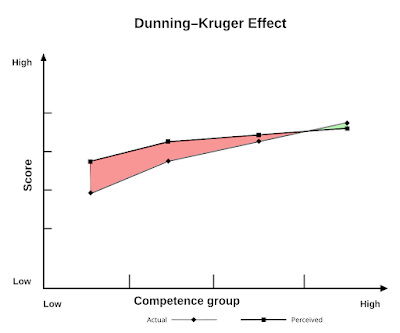

By now you have probably heard of the Dunning-Kruger Effect: A reliable finding across multiple domains of expertise, showing that experts on a topic know the limits of their own knowledge, but people who know only a little about it are unaware of their own limitations. This can also be stated in terms of a gap between one's competence in a topic area and one's confidence about it, with over-confidence being a typical characteristic of less-competent individuals. There is a slight tendency on the high end, as well, for experts to be overly pessimistic about their own performance, with their results on average tending to be slightly better than they give themselves credit for. The logical conclusion from this extensive body of knowledge is that one should probably evaluate people's expertise, rather than how confident they seem, in deciding whether to take them seriously or not.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is not enormous, by the way, even though it is statistically reliable. In popular culture, the effect has become exaggerated in the following type of diagram showing the process by which one develops expertise: Initially, confidence is shown to be near-infinite, in a peak that's dismissively labeled as "Mt. Stupid" on many charts. Then it is shown to fall abruptly into a "Valley of Despair," before finally increasing gradually on its way to a "Plateau of Competence."

This may be an amusing image for PowerPoint talks, but it's not an accurate reflection of the true Dunning-Kruger effect established by research. As shown in the image at the top of the post, people only slightly over-estimate their own knowledge at the low end of expertise, and even their overconfident self-ratings are lower than the self-ratings of experts. It may indeed take a long time for the gradual development of expertise, but the new learner is neither so inept nor so deluded as the corporate-trainer version of this effect implies.

One area where the Dunning-Kruger effect has been referenced is in public-policy debates about vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy has been in the news again due to a major measles outbreak in Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma that has led to multiple deaths. The vast majority of cases have been in unvaccinated people, because the vaccine against measles is more than 95% effective in preventing disease. At the same time, however, new U.S. Secretary for Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy has been actively casting doubt on the efficacy of common vaccines, suggesting that the measles deaths were the result of poor lifestyle choices, that natural immunity from infection might be preferable to vaccination, nutritional supplementation with Vitamin A can help to prevent measles (side note that it cannot: Vitamin A can be useful in infected children who are malnourished, but should not be taken preventively because it builds up in the body with potentially toxic effects). U.S. health agencies have also recently cancelled grants on vaccine acceptance and on the development of new mRNA vaccines, and removed information about vaccines from Federal websites (you might note that for my source about the efficacy of the measles vaccine above, I used a Canadian health agency's website). Kennedy also recently ordered the CDC to conduct a review of potential links between vaccines and autism, even though that proposed link has been widely discredited based on extensive scientific research. (Kennedy cited one cherry-picked study to the contrary at his confirmation hearing; even that study has been strongly critiqued on methodological grounds).

In this climate of doubt, more people are likely to refuse vaccines for measles and other preventable diseases. A global study in 2022 found that one of the strongest predictors of COVID-19 vaccine refusal was a lack of trust for medical information provided by authorities, and in the U.S. this type of mistrust was directly tied to political affiliation. Kennedy himself was found to be one of the top 12 sources of COVID misinformation on the Internet in a 2021 report. However, the tone had already been set in 2020, when a Cornell University report found that 38% of all COVID-19 misinformation on the Internet came directly from President Trump. People with greater exposure to misinformation about COVID-19 and COVID vaccines then were more likely to refuse the vaccines, with a correlation of r = -.77 between accurate COVID-19 vaccine knowledge and vaccine refusal -- an extremely strong effect.

Let's circle back, then, to the Dunning-Kruger effect. Is the gap between expertise and confidence in one's conclusions a reasonable explanation for why people refuse vaccines? The studies above suggest that it is not. As with many behaviors, Intuitive Mind factors such as values and group affiliations seem to be much stronger predictors of vaccine acceptance than knowledge or confidence in one's expertise. Furthermore, the knowledge-confidence gap identified by Dunning and Kruger is actually much smaller than suggested by popularized versions of this finding, and low-expertise individuals are not really as overconfident you might have been led to believe.

This is a good thing. It means that in order to improve vaccine intake, we don't primarily need to persuade people. And in particular, we don't need to "break through" false confidence, or lecture people with facts. Instead, we need to build trust, to work within people's social networks, and to appeal to people's core values and beliefs. These are all functions of the Intuitive Mind. Ultimately, it should be no surprise that Intuitive-Mind mechanisms are the key to increasing vaccine acceptance. As Two Minds Theory suggests, it is the Intuitive Mind -- rather than logic and fact-based decision making -- that controls behavior.

Comments

Post a Comment